Investors Watching Closely in the Wake of Recent Offshore Wind Announcements

Last week, I had the pleasure of speaking on a panel where we discussed financing for U.S. offshore wind projects to a full room at the 2018 Verge conference in Oakland. On that same day, my colleagues on the opposite coast joined nearly 1,000 others at the American Wind Energy Association’s Offshore WINDPOWER 2018 conference. One clear takeaway from both events is that the tide has turned for offshore wind, and people are getting excited about this next big step toward expanding the renewable energy economy.

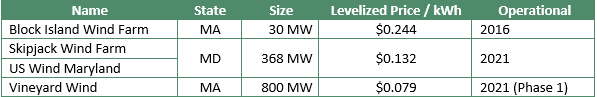

Offshore wind has seen a wave of major announcements in just the last three months. In August, ACORE member Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners announced record low pricing – far below experts’ projections – for the 800 megawatt (MW) Vineyard Wind project in Massachusetts. One month later, New Jersey announced the largest-ever solicitation for offshore wind in the U.S. at a whopping 1.1 gigawatts (GW), the first stage of a 3.5 GW by 2030 offshore goal. In early October, Ørsted, a leader amongst European offshore wind developers, entered into an agreement to purchase the U.S.-based company Deepwater Wind for $510 million, which adds another 3.3 GW to Ørsted’s existing 5.5 GW U.S. offshore project pipeline. The purchase includes the only operating U.S. offshore wind asset, the 30 MW Block Island Wind Farm.

The East Coast

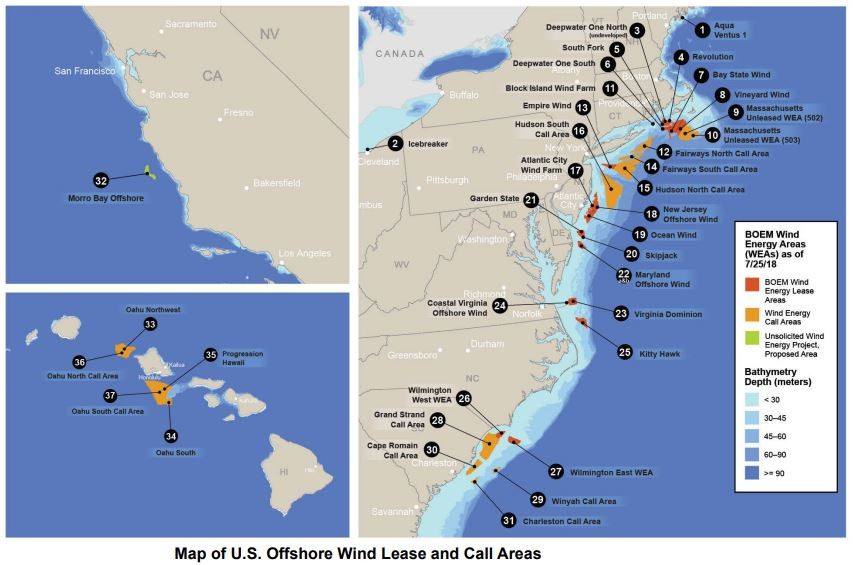

There are currently 28 offshore wind projects throughout the U.S that have been announced and are at some stage of the project pipeline, with a cumulative capacity of more than 25 GW. To put this into perspective, those 28 projects would be equivalent to more than one-third of all the solar capacity installed in the nation to date, and over one-quarter of all operating U.S. onshore wind. Five of those projects, totaling 1.9 GW, are actively under development and are expected to commence operations by 2023. While there are projects in the development pipeline in Hawaii, California and the Great Lakes, 23.4 GW of the 25 GW U.S. pipeline are located on the East Coast.

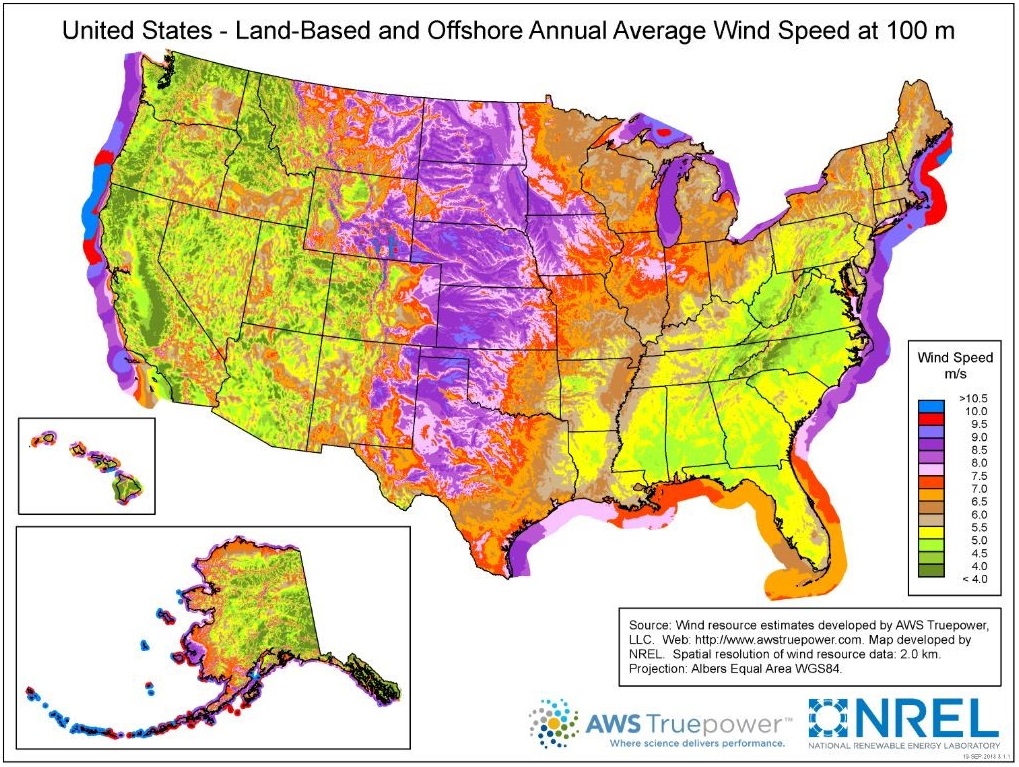

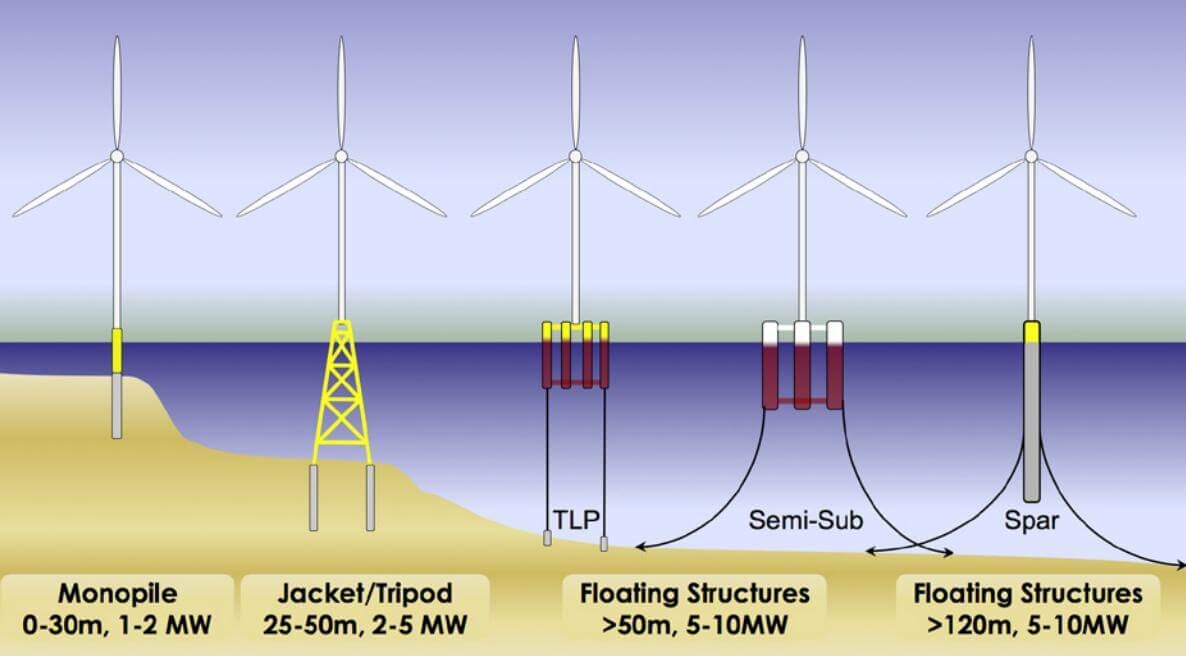

What’s driving these offshore projects? There are several factors and relevant developments. First, the resource potential is massive. Both the East and West Coasts have tremendous wind resources, with stronger and more sustained winds than the center of the country, which has enjoyed the majority of U.S. wind development. In fact, a Stanford study found that winds off the East Coast could theoretically supply one third of the total U.S. electricity demand. Furthermore, the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast coasts have a large, shallow and gradually sloping seafloor with strong winds, a perfect environment for traditional mounted offshore turbines that have already been proven effective at scale in Europe. This factor is why the East Coast is seeing early offshore wind announcements, in contrast with the West Coast, which will require floating offshore wind turbine technology that is currently less developed and more expensive than traditional mounted turbines.

The West Coast

The West Coast also possesses vast wind potential and has seen several important announcements in recent months. Winds on the West Coast have a technical potential of 112 GW and, given capacity factors, offshore wind could deliver 392 terawatt hours of electricity per year, which is about 1.5 times California’s current usage. Considering California’s 100 percent clean energy target, this is a resource that cannot be ignored. However, due to the topography of the Pacific’s seafloor, offshore wind projects must use “floating” turbine structures. This relatively new technology is more expensive than the traditional “monopile” turbines, though costs have been declining rapidly in Europe. Additionally, the U.S. Navy has declared large swaths of viable West Coast waters as wind exclusionary zones not open to development.

These impediments have not deterred the West Coast offshore wind industry. In fact, a number of promising announcements this year have put wind in the sails of West Coast developers. Earlier this year, Statoil (now Equinor) announced that their floating wind farm Hywind in Scotland surpassed expectations and achieved an impressive 65 percent capacity factor, almost double the average for a U.S. onshore wind project (37 percent).

In California, an unsolicited proposal for a floating offshore wind project by Trident Winds off Morro Bay had stalled due to Navy exclusionary zones. However, two weeks ago Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke released a call for information and nominations to identify offshore wind projects in this area. This sends a signal to the Bureau of Ocean Management (BOEM) to find a way to reconcile these exclusionary zones with the Department of Defense and find suitable sites for California offshore wind projects. Further north, the Redwood Coast Energy Authority, a community choice aggregator in Humboldt County, submitted an unsolicited bid in September to BOEM for a lease to develop a floating offshore wind project. These impediments have not deterred the West Coast offshore wind industry. In fact, a number of promising announcements this year have put wind in the sails of West Coast developers. Earlier this year, Statoil (now Equinor) announced that their floating wind farm Hywind in Scotland surpassed expectations and achieved an impressive 65 percent capacity factor, almost double the average for a U.S. onshore wind project (37 percent).

Policies Driving Offshore Wind

The flood of proposed projects and positive announcements is encouraging but should be kept in perspective. The European market is nautical miles ahead of North America, placing more than 1 GW of new offshore wind in service annually since 2012. So why the sudden U.S. move into the offshore market now? As with other renewable technologies, a recent dramatic reduction in costs has been a major driving factor. Ørsted reported a 63 percent offshore wind cost decline from 2010 to 2016. In fact, European prices are projected to drop another 67 percent by 2025. The U.S. only has a few announced prices so far, but it is experiencing dramatic price reductions as well.

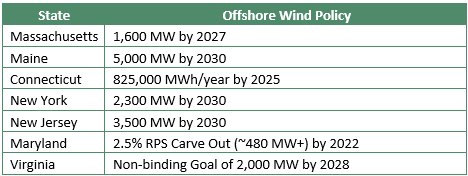

In the early 2000s, European countries launched a series of supportive policies that fostered early offshore wind projects. These frontrunners established the necessary pipelines and eventually reached economies of scale. Now, we are seeing announcements of offshore wind projects in the EU without subsidies that can compete with all sources of energy. Meanwhile, in the United States, aggressive state renewable and climate policies are driving the early offshore wind market.

There is a space race of sorts happening right now on the East Coast for offshore wind, with coastal states competing to establish themselves as hubs for offshore wind project development and beneficiaries of the massive associated investment and economic growth. Offshore wind development requires specialized manufacturing, modernized deep-water ports and specialty ships that are compliant with the Jones Act. This unique supply chain does not currently exist in the U.S., and those states that can establish themselves in this sector will reap substantial economic rewards. On top of these supply-chain benefits, local offshore wind development can bring thousands of jobs. The potential benefits of offshore development are summarized in a recent report by Environmental Entrepreneurs.

Additionally, offshore wind is an immense renewable resource that can be sited close to major load centers in states that have set ambitious renewable energy targets. The importance of offshore wind as a tool to meet renewable energy, climate and economic development targets is especially important considering the difficulty of siting new onshore projects in many of these same environmentally oriented states. These states have used a variety of mechanisms to reach their offshore targets, including establishing offshore wind renewable energy credits and directly facilitating power purchase agreements between developers and the states’ utilities.

Financing Offshore Wind

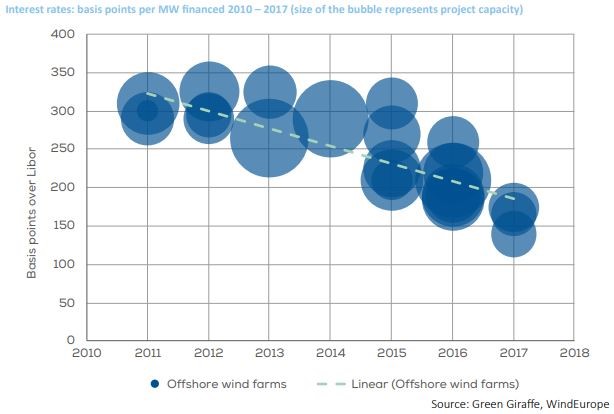

States’ supportive offshore wind policies have guided developers and investors as they have worked to create a strong project pipeline. However, such massive projects require significant upfront capital investments. European banks, investors and capital markets have become increasingly comfortable with offshore wind as an asset class. While much depends on project specifics, on average in Europe there has been an increase in the debt to equity ratio, with between 70 to 80 percent debt and 20 to 30 percent equity for offshore projects. Furthermore, the cost of debt capital has come down over time as lenders recognize offshore wind can provide a low-risk, secure and steady value stream. This is especially important given the increasing demand today for safe, profitable green investment at scale.

Declining Cost of Debt for European Offshore Wind

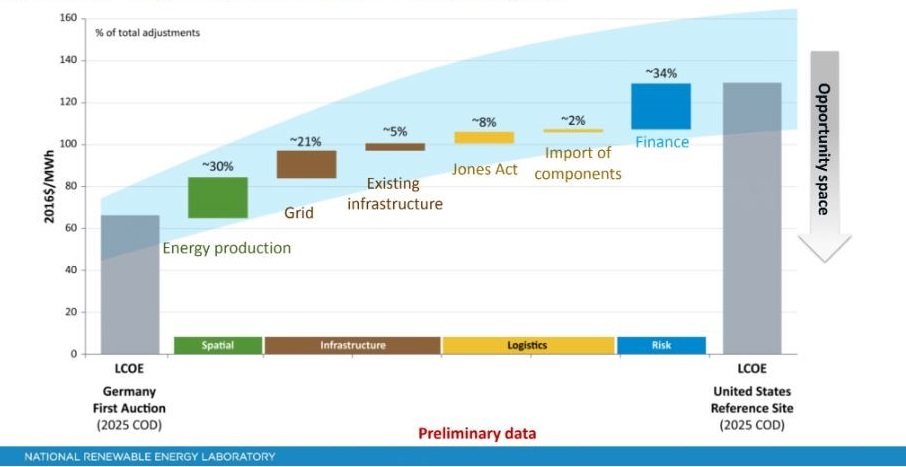

Reducing the cost of capital for U.S. projects is critical to the effort to enhance the cost effectiveness of offshore wind. In fact, finance was identified as the number one opportunity for cost reductions in offshore wind prices in a recent National Renewable Energy Laboratory study (see chart below).

Key U.S. Offshore Cost Challenges

Key Questions Moving Forward

A number of important questions remain regarding the financing of projects off America’s coasts:

- What will project capital structures look like for U.S. offshore wind projects? Will we see similar debt to equity ratios or the same capital evolution as Europe?

- How will the existence of tax equity (not used in Europe) affect the capital stack for early projects that may be able to capture the investment tax credit and production tax credit? Will traditional tax equity investors be able to accommodate the longer construction times of offshore wind compared to solar and onshore wind?

- Will the cost of capital be comparable to existing markets?

- Who will be investing in these projects? Will European investors be active in the U.S. market as well? Will institutional investors enter the space at an early stage? Will it take time for capital markets to get comfortable with offshore wind?

Over the next several months, ACORE will turn to these unanswered questions and work with our members on analyses to promote a better understanding of the issues surrounding financing for U.S. offshore wind, and to help accelerate investment in the sector.

Join leaders from across the renewable energy sector.

What will our next 20 years look like? Here’s the truth: they’ll be better with ACORE at the forefront of energy policy.

Shannon Kellogg

Amazon Web Services (AWS)