Incorporating GETs and HPCs into Transmission Planning Under FERC Order 1920

Download a two-page summary of key takeaways from the report here.

Prepared by T. Bruce Tsuchida, Linquan Bai, and S. Ziyi Tang of the Brattle Group and Jay Caspary of Grid Strategies for the American Council on Renewable Energy.

Executive Summary

The energy landscape in the United States is currently undergoing an unprecedented transformation. Rapid technology developments and fast-emerging new loads – from data centers and cryptocurrency mining to electrified transportation and industrial processes – are reshaping electricity generation, consumption, and delivery. This transition requires a massive expansion of the electric transmission grid, with estimates suggesting that transmission capacity must double or triple in the coming decades.1 In addition to these extraordinary transmission needs, the pace of expansion must accelerate to fulfill near-term grid demand.

Such seismic shifts will also require the nation’s transmission providers to update their transmission planning processes. Transmission providers must not only plan for future needs but also factor in the uncertainties surrounding the industry – including those associated with costs and schedules of the transmission investments, and the possibility that new loads either do not materialize or may grow at an even more rapid pace than projected.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC’s, or Commission’s) recent Order 1920 and its subsequent order on rehearing, Order 1920-A, mark a critical milestone in addressing these challenges by mandating scenario-based, long-term transmission planning. Among other mandates, Order 1920 requires transmission providers to (1) develop at least three plausible and diverse scenarios that identify both long-term transmission needs and potential solutions, (2) quantify the benefits of the potential solutions, and (3) establish an evaluation process for selecting among the potential solutions.

Order 1920 does not prescribe the details of scenario development, evaluation processes, or selection criteria for assessing future transmission solutions; instead, it leaves them to the respective transmission providers to submit to the Commission for approval. However, the Order does provide certain broad standards that these criteria must meet – primarily that the evaluation processes must aim to ensure the selection of more efficient or cost-effective facilities and that the benefits must be weighed against the costs.

Order 1920 does ask transmission providers to consider alternative transmission technologies (ATTs) as part of their potential solutions.2 ATTs discussed in the Order include certain Grid-Enhancing Technologies (GETs) – namely, Dynamic Line Ratings (DLR), Advanced Power Flow Control (APFC), and Transmission Switching – as well as High-Performance Conductors (HPCs).

ATTs are cost-effective, scalable, and faster-to-implement technology choices when compared to traditional wires-based solutions, such as building new lines on new paths, reconductoring existing lines using conventional conductors, or building parallel lines to increase transfer capability within an existing path. And, despite the several barriers that must be navigated to prevent underinvestment in ATT solutions, Order 1920 presents significant opportunities – particularly for states – to enhance the consideration of ATTs and promote their broader adoption.

In this report, we aim to highlight both the pitfalls and opportunities of ATTs. Specifically, we cover the benefits of ATTs (focusing on GETs and HPCs), how current planning processes may be inadequate for consideration of ATTs, and how Relevant State Entities (RSEs) – defined as any state entity that is responsible for electric utility regulation or siting electricity transmission, or another entity designated by state law – can encourage transmission providers to integrate ATTs into their transmission planning and selection.

BENEFITS OF ATTS (SEE SECTION II)

ATTs have three distinct key characteristics when compared to traditional wires-based solutions. These are:

✓ Lower cost and faster installation

✓ Complementarity to existing equipment

✓ Portability and reversibility (for GETs only)

Integrating ATTs (which may include other technology options as determined by transmission providers since Order 1920 is not restrictive to the technologies that are specified) into long-term transmission planning provides numerous benefits, including, at a minimum, the “Seven Benefits” Order 1920 requires transmission providers to consider when evaluating and selecting transmission facilities:3,4

✓ Benefit 1: Avoided or deferred reliability transmission facilities and aging infrastructure replacement

✓ Benefit 2: Reduced loss of load probability or reduced capital

costs to meet planning reserve margin

✓ Benefit 3: Production cost savings

✓ Benefit 4: Reduced transmission energy losses

✓ Benefit 5: Reduced congestion due to transmission outages

✓ Benefit 6: Mitigation of extreme weather events and unexpected system conditions

✓ Benefit 7: Capacity cost benefits from reduced peak energy losses

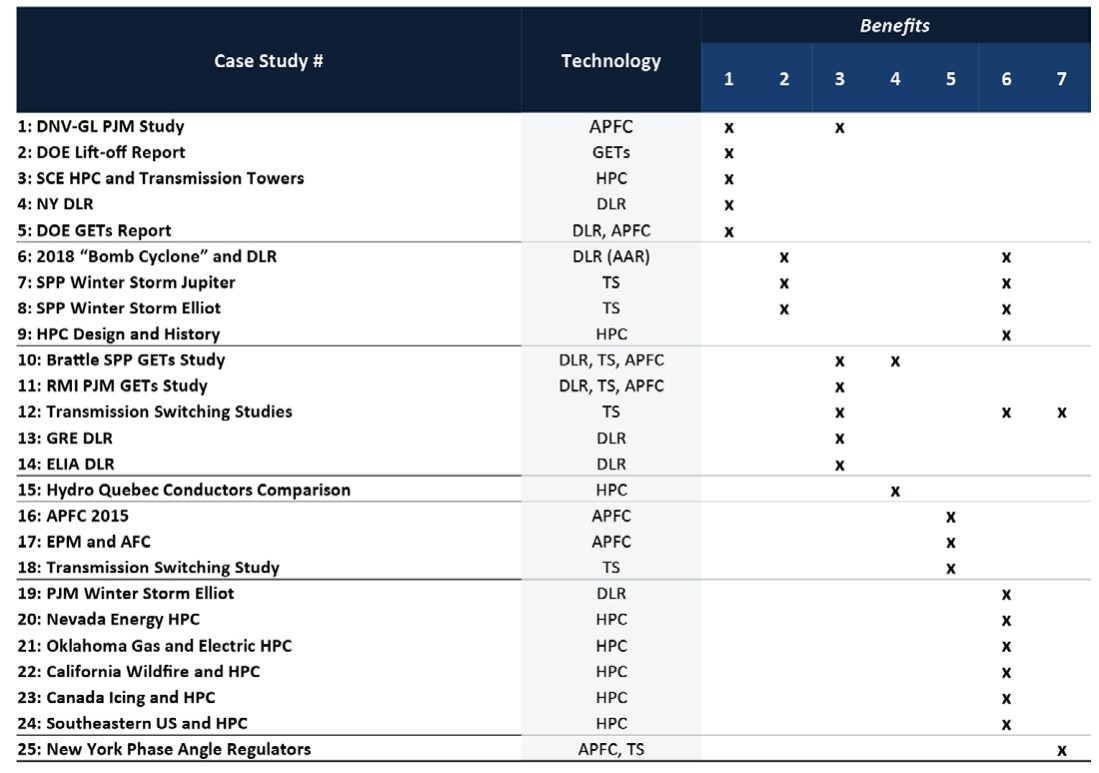

A review of 25 case studies of ATTs (limited to those specifically listed in Order 1920) shows that each of the Seven Benefits can be provided by ATTs. Figure ES-1 summarizes the 25 case studies, including which ATTs were used and the Benefit(s) – numbered 1 through 7, corresponding to the above list – that were observed. Each implementation may have shown other benefits either not captured in the Order 1920 list or not quantified in the report.

The table shows that ATTs are capable of providing all of the Seven Benefits. The vintages of some of the case studies show that ATTs are proven and mature technologies, making them viable solutions for improving and expanding the transmission system efficiently and reliably.

CURRENT PLANNING PROCESSES AND ATTS (SEE SECTION III)

The current deterministic framework used for transmission planning – which is built on static future snapshots – may not be adequate to evaluate and compare the Seven Benefits of Order 1920. A more holistic approach that considers different timeframes, alternative system conditions, and an evolved evaluation methodology and selection criteria is needed.

For example, some of the Seven Benefits (including Benefits 1 and 7, and, to some degree, Benefit 2) can reduce investment needs and may be captured in current planning processes that compare investment cost options. However, others – like Benefits 3, 4, and 5, which could immediately lower customers’ bills – are more operational in nature and require a more granular analysis (e.g., hourly) over the operational timeframe rather than the longer planning horizon. Benefits 5 and 6 are temporal events that further require the evaluation of alternative system conditions for shorter timeframes.5

The evaluation methods and solution selection processes, which often compares potential solutions, also need to be carefully implemented to ensure the broad suite of benefits ATTs provide is fully considered. An evaluation methodology that looks across all Seven Benefits (rather than on an individual benefit-by-benefit basis) is required since – even if the scoring for an individual Benefit is mediocre for a given solution – the sum of multiple Benefits may outweigh other solutions that score high in just one Benefit.

Furthermore, certain ATTs, including GETs, may not be directly comparable to other potential solutions. For example, comparing a new line to a GETs-alone solution (such as DLR) over a 20-year period misses the point. In this example, the more appropriate comparison would be a new line without GETs to a new line supported by GETs.

These observations highlight the complexity of evaluating the Seven Benefits across various technology options, including ATTs. The challenge of developing a comprehensive evaluation methodology and criteria could become a hurdle for implementing ATTs and other non-traditional solutions into the planning process. In addition, a review of the current (i.e., pre-Order 1920) planning processes identifies four barriers to implementing ATTs:

- Insufficient recognition of the ATTs themselves;

- Misaligned incentives;

- The use of traditional planning approaches that tend to be static and deterministic; and

- The perceived lack of standardized data, tools, and analysis methodologies, along with human resources capable of carrying out advanced analyses.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR RELEVANT STATE ENTITIES (SEE SECTION IV)

Order 1920-A assures that RSEs can demand greater transparency and flexibility in the long-term regional transmission planning processes. The amendment allows RSEs to engage in the evaluation process by offering inputs on the evaluation methodology and selection criteria, contributing to scenario development, or suggesting additional scenarios and/or benefits for the transmission provider to consider during the solution selection process.

Orders 1920 and 1920-A also provide RSEs and transmission customers the option to voluntarily fund part or all of the cost of a proposed transmission solution. This option could improve the selection process for ATTs if the transmission provider’s evaluation process includes relevant and appropriate measures, such as a benefit-to-cost ratio criterion.

For RSEs to fully take advantage of these levers provided by Order 1920-A, they must recognize the aforementioned implementation barriers together with the benefits ATTs can provide. Benefits are not limited to the Seven Benefits outlined in Order 1920; they can extend to benefits associated with certainty, time, and optionality.

For example, GETS can offer immediate remedies to issues like congestion while providers plan for more permanent solutions (e.g., new wires), without concerns about the new GETs assets becoming stranded. Here, the GETs investments – which often have payback periods of months rather than years – not only solve the existing issue but can also offer transmission providers additional time needed to best plan for the future. Although the value of such time-associated benefits (i.e., avoided risks) is more challenging to quantify in monetary terms and will vary by transmission provider and needs, they should be considered in planning activities moving forward.

Moreover, RSEs should recognize that transmission providers may not prioritize cost-avoidance as covered by Order 1920’s Seven Benefits because transmission costs are typically passed through to customers – meaning transmission providers (both operators and owners) may have limited incentives to pursue transmission or technology solutions that produce cost-savings for customers.6 Thus, states may need to directly engage with transmission providers to ensure that cost-saving solutions are not overlooked during the transmission planning and solution selection process. States should explore policies and incentives that would further encourage transmission providers to pursue lower-cost solutions.

By introducing and discussing these topics with providers and

other stakeholders, RSEs could significantly impact transmission

planning, especially the selection process. States can encourage

transmission providers to be technology-neutral and cost-conscious in a collaborative way while remaining objective and focused on state initiatives and consumer protection.

To encourage transmission providers to consider ATTs in their planning, RSEs could request transmission providers consider a reasonable number of additional scenarios – beyond the minimum three mandated in Order 1920 – in their planning that include ATTs.7 Additionally, since Order 1920 also requires the transmission providers to consult with and seek support from the RSEs when developing the evaluation process and selection criteria,8 RSEs could advocate for the inclusion or omission of certain selection criteria; for example, RSEs could request removing any criteria that would bias the selection process against ATTs – such as qualitative criteria that are subjective and difficult to evaluate, or rankings solely based on maximum net benefits – without any consideration for benefit-to-cost ratios.

With these options available, RSEs could effectively develop a preferred loading order for transmission selection that aligns with state priorities. Examples of such loading orders may prioritize lower-regrets solutions or higher benefit-to-cost ratios. Lower-regrets options may include solutions that provide future optionality (e.g., replacing an existing substation with one that – compared to the original design – uses more flexible arrangements, such as a ring bus or double bus design, to provide more expansion options). “Right-sizing” is often a lower regrets option.9 For finding such solutions, the selection process may focus on mitigating costs and the associated risks of not proactively right-sizing (by looking at the longer-term rather than immediate upfront costs).

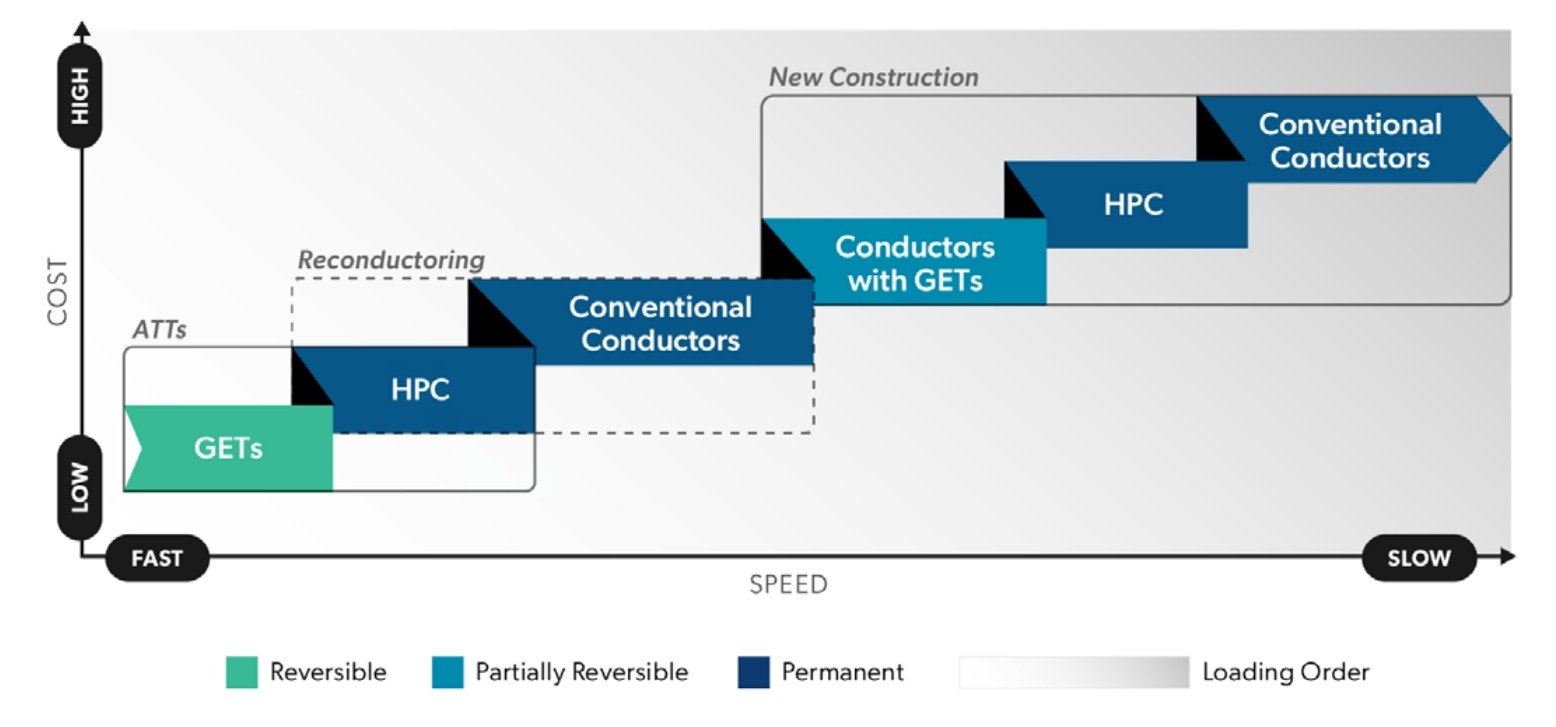

A higher benefit-to-cost ratio can be achieved by first optimizing the existing grid, such as by using GETs; then upsizing existing lines, such as through HPCs; and finally adding new lines using conventional technologies or HPCs when ATTs alone do not make sense as standalone solutions, as illustrated in Figure ES-2.

Part of this exercise may require establishing “rules of thumb” to help evaluate potential solutions at a high level (more for screening purposes), such as prioritizing GETs for transfer increase needs of 25% or less and prioritizing HPCs for transfer increase needs of 50% or more or when “right-sizing” opportunities are observed. A pre-screening cost threshold (e.g., normalized in $/MW investment costs) could also be developed for this purpose.10 It should be noted that any rules of thumb or heuristics start broad and are then refined and updated later as transmission planners gain more experience in evaluating various technologies, including ATTs.

As we explore in this report, integrating ATTs into transmission planning and selection is not just an opportunity, but a necessity for achieving cost-effective, timely, and sustainable grid development over the next several decades. FERC’s framework provides a strong foundation, but proactive efforts from all stakeholders will be essential to overcome barriers, realize the full potential of these technologies, and accelerate the industry transition.

The success of Orders 1920 and 1920-A will depend on the willingness of transmission providers to embrace these innovative solutions, modernize their frameworks, and deliver a grid development plan that is reliable, efficient, and ready for the future. Active and collaborative engagement from RSEs, combined with their guidance to ensure accountability for transmission providers, will be essential for achieving success.

Join leaders from across the clean energy sector.

What will our next 20 years look like? Here’s the truth: they’ll be better with ACORE at the forefront of energy policy.

Shannon Kellogg

Amazon Web Services (AWS)