Explaining Changing Trends in Cleantech Patent Filing with Kilpatrick Townsend’s Scott McMillan and David Hsu

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”30px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]June 12, 2019

by Tyler Stoff, Policy & Research Manager with ACORE

Patent litigation and prosecution firm Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP and patent consultants GreyB Services recently released their first annual Patenting Trends Study. Their findings documented changes in filing behavior from 2008 – 2018. ACORE staff interviewed Kilpatrick Townsend Partner Scott McMillan and Associate David Hsu to better understand the impact of these trends on the renewable energy industry. This interview has been compressed for clarity.

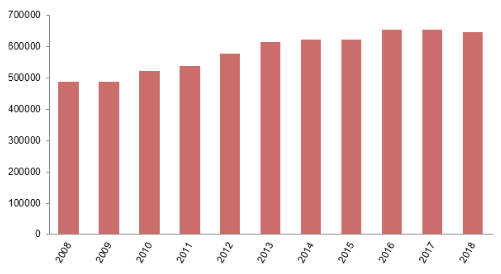

ACORE: Thanks for sharing your new study on patenting trends in cleantech, or environmentally beneficial technology. Reading the report, it looks like cleantech patent filings peaked as of 2011 as overall patent applications continued to grow. Are we understanding that correctly?

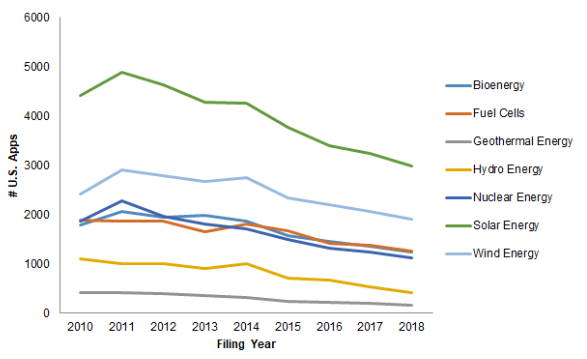

KT: That’s generally correct. Overall patent filings in the cleantech area did decrease from a peak in 2011, and that’s primarily a result of a decrease in patents for clean energy “harvesting” or generation technologies.

ACORE: Why do you think we’ve seen this decrease in patent filings for cleantech amidst an overall increase in patent filings among other industries?

KT: One possible explanation could be the U.S. stimulus package running out as of 2011. In 2009 and 2010, some of those early data points in this study, patent filings actually went up even though the country was in a deep recession. So, one potential takeaway is that government stimulus in the renewable energy space could have increased the number of patent filings during that time.

Another possibility – and this is going to be a lot of speculation – is cost-competitiveness. At least for wind and solar, now that cost curves are reaching lower levels, maybe there’s a tradeoff. Right now, if you build more wind and solar, even if it’s more advanced, you’re not going to achieve as much of a decreased cost per kWh as before, so it’s almost more cost-effective just to deploy. Electricity is a fungible good. Being so fungible is different from other technologies like artificial intelligence and automotive where you can get some additional feature that might be realized commercially because of a patent.

ACORE: That’s fascinating. So it sounds like the incentive for the kinds of innovation that patent filings represent might be bigger at earlier stages of development, where the financial payoff for innovation is higher. When you get to a level of cost-competitiveness where you can offer wind at two cents, the incremental gain to justify the next investment just isn’t there. Maybe some of the other technologies that are seeing more activity are closer to where wind and solar were ten years ago. One thing that’s closer to where wind and solar were then is energy storage. The results of ACORE’s recent $1T 2030 survey showed that energy storage is the #1 area that our members are interested in investing in. Were you able to break out the degree to which there’s patent activity in energy storage?

KT: For the taxonomies used in the study, it wasn’t clear where storage fit in. But we think that would be a very interesting thing to look at, and we hope next year’s study will be able to draw that out. Storage may not necessarily be reflected in the larger energy harvesting numbers.

ACORE: Your study proposes that an increase in patent filings is a good thing for the sector to which those patent filings apply. Over what time period do you think that’s true? The patent filing peak for cleantech was 2011, but we’ve had some pretty explosive deployment since then. What’s the timeline after which you would expect an increase in related economic activity? Or conversely, if filings are starting to fall, what’s the timeline after which you would expect to see a decrease in related economic activity?

KT: What typically happens is companies tend to file patent applications prior to public disclosure, prior to rolling out their product. This is primarily due to the fact that in most countries, if the inventor discloses their invention publicly before filing a patent application, they might waive their ability to file a patent on that invention. Therefore, patents tend to be precursors, which is again one of the takeaways from the study. How early the patent precedes the actual product may vary from product to product. In the electronics industry, things tend to be developed very fast, so patents may predate the product itself by just a matter of months. Whereas in other industries, automotive for example, it could take much longer.

ACORE: Do you have any sense of the timeline for renewable energy? It sounds like you’re saying, at a minimum, longer than electronics?

KT: Probably. That’s our speculation, but it’s not something we can take away from this study.

ACORE: Given that our audience is the greater renewable energy community, what lessons do you think they should take away from these findings?

KT: Not all cleantech is on a downward trend. Electric vehicle and energy efficiency patent filings increasing, and it does seem like the stimulus likely played a role in the increase in cleantech patent filings.

ACORE: What do you think the future looks like for renewable energy patenting? If the thesis is true that more patent filings are good and fewer patent filings are bad, what policy steps or market dynamics might help reverse that trend?

KT: Predictions are hard, especially of the future. Our feeling is that the industry is vibrant and dynamic now, particularly at startup companies. The economy overall is better. Maybe there is more capital involved. There’s always going to be room for innovation, even in industries that are cost-competitive. There are just more companies and more investors and more interest in the renewable energy area. There is more activity from some of our clients than maybe in past years. There is still opportunity for more technology development. Even though maybe from a policy standpoint there aren’t top-down federal policies that will encourage more carbon-efficient energy production, there are several state-level programs that do that. The public is more and more aware and concerned about climate change. There’s still a lot of opportunity for growth in the policy space.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Join leaders from across the clean energy sector.

What will our next 20 years look like? Here’s the truth: they’ll be better with ACORE at the forefront of energy policy.

Shannon Kellogg

Amazon Web Services (AWS)